Hey there, welcome to part three of this 101 series.

In case you need a little orientation, here’s where we are in the series:

Part 1: Intro to Circular Design to regenerate nature

Part 2: Design products with knowledge, purpose and highest value

Part 3: Work within the constraints of a circular material strategy- you’re here now

Part 4: Create a plan for use cycles and end of life (at the design stage)

Keep in mind that we’re unpacking Circularity at the Product Design level (and not yet looking at Circular Business Models or Systems). Revisit Part 1 & 2 for bigger explainers on that.

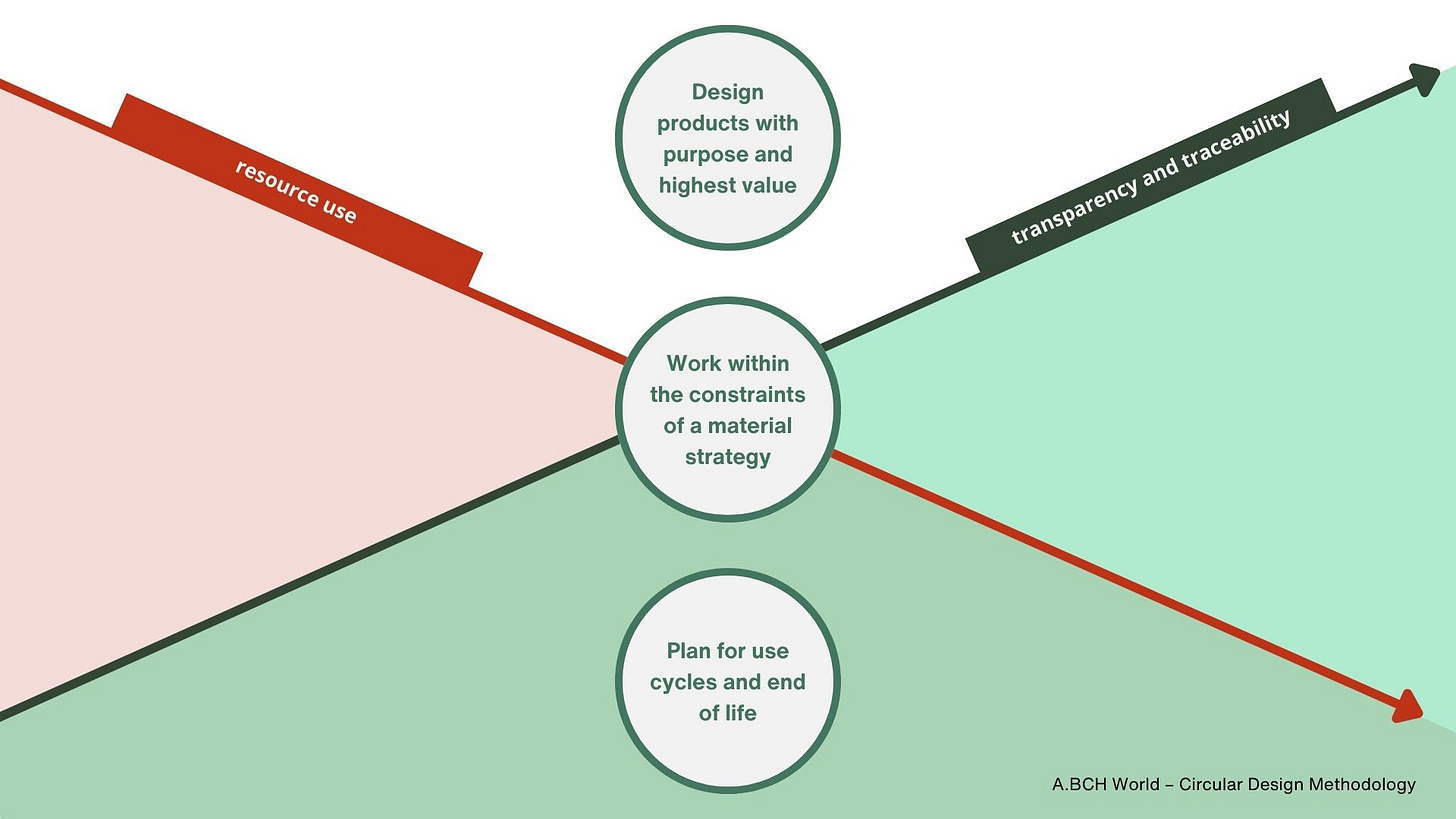

Design to Regenerate Nature - my approach as a circular design practitioner

Product Design Actions:

Design products with knowledge, purpose and highest value

Work within the constraints of a circular material strategy

Create a plan for use cycles and end of life (at the design stage)

Ongoing Process Actions:

Increase the transparency and traceability of materials and products

Decrease resource use (eliminate use of virgin non-renewable resources)

Here’s a big picture view of these actions:

Today we land on Stage 2 so if you missed Stage 1 or the Introduction, jump back to the links above to get the full story.

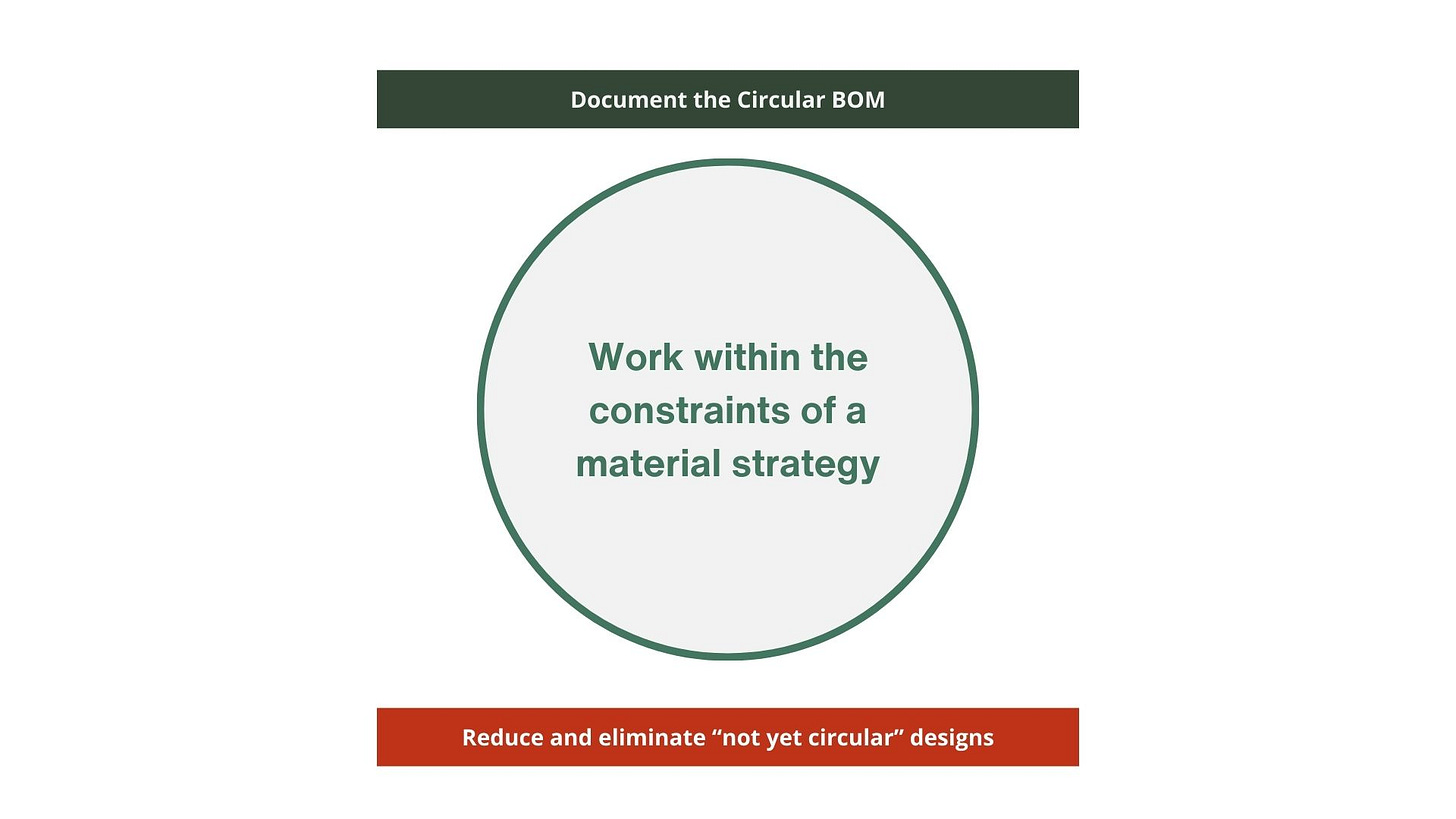

Stage 2: Work within the constraints of a material strategy

Last week we talked about designing products with knowledge, purpose and for highest value. We edged into the philosophical, asking ourselves, should this product be made? The next stage takes a much more binary approach. We have moved from the blending of emotional and physical qualities that makes something durable by design into - is this thing materially circular or not?

With that said, the primary design action is to select the correct material strategy for the product purpose.

Alongside this we will increase the documentation of materials and the supply chain while decreasing any “Not Yet Circular” products put on the market by rethinking their need to exist and probably returning to the product purpose part of Stage 1.

So what are circular material strategies? There are two key concepts to understand initially, and these link directly to a better outcome in the use and end of life phase.

The first is Monomaterial, defined as a material or product that consists only of one (100%) of the same fibre or contents.1

The second is Simple Disassembly, which is a defined strategy for products to be easily pulled apart into material constituents at a particular phase in the product lifecycle. “Simple” is understood as a combination of low complexity and a minimal number of disassembly tasks required and these must be outlined explicitly in the design phase. Disassembly allows for materials to re-enter the Reuse or End of Life phases.

The 6 Circular Material Strategies:

Biological - Monomaterial

Technical - Monomaterial

Biological - Simple Disassembly

Technical - Simple Disassembly

Mixed - Simple Disassembly

PolyCotton - Simple Disassembly

Everything and anything else:

Not Yet Circular

Definitions for each of these strategies can be found in the upcoming Refashioning Circular Design Guide, slated for a 4th March 2025 public launch (I have just realised this might be sold out, so please comment “Refashioning” below if you missed out and I’ll send you a link to another similar event when it’s live).

Inputs & Finished Product

We also need to consider, as designers, that we are working with both Inputs (individual building block raw materials that make up a product) and a Finished Product. The chosen material strategy will apply to the Finished Product, but it must flow on to every input we decide to use in that product.

Finished Product:

Inputs for Finished Product (stay within the strategy):

Inputs, Circular Inputs, Traceability and Chemistry

Inputs can be either, circular by definition - that is, renewable, and/or recycled and/or reused, or they can just be inputs - anything that does not fall into one of those categories in its entirety. The term ‘circular inputs’ doesn’t mean there is no environmental impact or even that there is no pollution associated with it. The term simply means the inputs are originating from a resource that is either from waste (recycled or reused) or can be regrown in the same soil (renewable).

That is simplistic on purpose. After all what does renewable mean? Does it mean that every single input and output used and generated in the production of the raw material input must also be renewable? An example here could be the input of synthetic fertilisers on the soil, used to grow the cotton - this cotton becomes an input for your product - so is it technically not renewable? Unfortunately this is a little fuzzy - I recently attended a course on the new Circular Economy ISO standards, and it still remains fuzzy. What seems to be important is the traceability of the input, whereby every stage in the supply chain would declare their inputs to make their part or process of a raw material. Those fertilisers would ultimately fall under the circularity disclosure of the farmer and the data would be passed on through the supply chain.

However, from the product design perspective, I approach this rather pragmatically, because otherwise you will end up in a spiral where nothing is acceptable. So try this on for a circular input rationale:

Anything remaining on/in/with the raw material input is what designers should count as part of the input. Example: synthetic fertilisers do not remain intact in the final cotton textile. In contrast, formaldehyde anti-wrinkle fabric treatments or chemicals like PFAFs, will.

This can and absolutely should become stricter and more comprehensive over time. For example, when an LCA is done on a particular material, depending on its goal and scope, it’ll highlight areas where inputs, processing and management of outputs can be improved on. You’ll look at this more from an impact reduction lens than a final product’s circularity potential lens. From a designer/product level, this can be tricky to initiate and much of the work will need to be undertaken from a facility level or company wide level, requiring larger work that is less product specific and more process and system specific.

For the purpose of this 101, the circular input rationale is a starting point to help prioritise product inputs from non-finite resources. Use LCAs to determine where impact reduction might be made next. Finally, research and document everything you can to find out what remains intact with each of your inputs, and lean on traceability and chemistry certifications wherever possible to back up your assumptions.

Now there is a hierarchy of choice here - first within the strategies. Monomaterial will yield a higher quality feedstock at End of Life and highly feasible decommissioning (an essential yet often ignored aspect of End of Life). Simple Disassembly is a little more complex, and reduces the likelihood of feasibility but if designed well, can still yield highly circular material outputs. PolyCotton Simple Disassembly has the most limited circular end of life options and maximum effort and resources for disassembly and therefore, feasibility is further reduced. So there’s that. And by the way this is snapshotting the current state (not the potential). As End of Life options improve and scale over time, so might the strategies be updated.

Next is the hierarchy of inputs. Circular material strategy comes first. It frames every material used in your product. Do not be seduced by a 50% recycled PET 50% organic cotton jersey for your t-shirt design if you are aiming for Biological Monomateriality. Strategy first, circular inputs second. If you can’t add any circular inputs yet but you can still meet the material strategy - this is okay! Now you know exactly what to hone in on and research/improve for next time.

You might ask, why does this matter? When we zoom out to the bigger picture of WHY less than 1% of textiles are recycled, we see a picture of too much low value crap entering the system and too low of incentives for circularity realisation. When we design within the Monomaterial or Simple Disassembly strategies, we’re making the materials more valuable and easier to reclaim. And that means better quality materials re-entering the system for our future circular inputs. We’re investing into our own future feedstock. Quality in = Quality out = Quality in.

Now, try as you might, sometimes you just can’t get the circular material strategy to work. Perhaps you’re missing a critical input fitting within the strategy, other times the product purpose cannot be achieved within the strategy yet. This highlights innovation gaps, and while your product will fall under ‘Not Yet Circular’, you too will know what needs further research, development and improvements for next time. Everyone can play within this circular design approach.

Understanding Product Purpose requirements through testing

You may be making some pretty significant changes to your products by trying to fit them into a circular material strategy. What’s important is that you test any changes against your Product Purpose requirements. Making things of high quality is paramount, but there is no need to over-engineer things that don’t need it (ie. polyester thread in a cotton t-shirt).

There will likely be some tradeoffs to those of conventional performance when it comes to designing for the really ambitious strategies (like Biological Monomaterial - it’s challenging!). This shouldn’t be abandoned if it gets hard. There are so many ways to innovate within the constraints of the material strategies, but it’s not usually a like-for-like situation. Materials swaps to achieve a circular material strategy need to be well considered and designed for.

There will be some common things to look out for, test and iterate (this is the fun part of design after all). Here are some of the things we learned to test for through designing within the Biological Monomaterial and Simple Disassembly material strategies at A.BCH:

– Seams

– Material Structure

– Fibre Properties

– Finishes

– Seam Placement

– Closures

Stay tuned for more details on testing methods and considerations in the Refashioning Circular Design Guide.

Documentation and the Bill of Materials

Ahhh documentation. It really is crucial to circular design, especially at this point. If we go to the end of the lifecycle, the only way a recycler is going to know the best end of life solution for your product, is if there is a clear record of every input used in the garment. This speaks to any other user or value chain provider in the lifecycle too - from wearers to repairers, remanufacturers and everything in between.

Outline your Bill of Materials (BOM). This can be done in a spreadsheet, or through your PLM software provider. Very soon, I’ll be launching a software tool in collaboration with Style Atlas, called Quadrant Circular. This has been built to make the documentation part, not just within the BOM but also within the entire Circular Design process, streamlined. If you want access to this tool, comment “Circular Quadrant” below and I’ll let you know as soon as it’s live.

So. What if we can’t design for circularity right now? There are specific actions you can take with ‘Not Yet Circular’ products to make them better candidates for transitioning.

Some tips include:

Sourcing from surplus materials (a Reused circular input, even for Not Yet Circular Product) from trusted material marketplaces like Queen of Raw (USA), Last Yarn (UK) or Circular Sourcing (APAC) - consider not just for fabrics but for all inputs like threads, interlinings, yarns and trims

Starting to use circular inputs as part of a greater sourcing shift to better materials (remember: these are Renewable, Recycled, Reused), even if they don’t align together under one strategy just yet - this builds your materials library and may help you achieve a circular material strategy with other products and can share in resource use

Creating strong use cycle plans (covered in the next part of the Circular Design 101 series) that outline the maximum uses for the product in both High and Low Cycles of Use

Focus on the business models that would invest in and enable the Cycles of Use

Bring it all back to…nature

So how does this step regenerate nature? At the simplest level, we are prioritising materials that don’t clog the natural system. No matter how beautiful and long lasting a product you design (and yes that is important - I talked about it first in Stage 1), if the materials are not able to be reclaimed and reutilised without waste, or digested through natural systems, they will inevitably still end up in landfill. This is a fact!

Many organisations have promoted a choose-your-own-adventure type of circular design, they say to choose between slowing the flow (make good stuff that lasts) and close the loop (make stuff that nature can process and/or that can be recycled). My challenge to you is… Why can’t we do both?

In fact we must do both to realise a circular economy for clothing.

Thanks for reading! Like, Comment, Question, Share etc. I’d love to grow an actively engaged community around this topic.

The next post is all about Phase 3 which for the purpose of this Circular Design 101, will include planning for Use Cycles and End of Life. See you next week.

All my best,

Courtney

(Holm, C., Boulton, J., Payne, A., Samie, Y., Underwood, J., Van Amber, R., Islam, S (2025). Refashioning: Accelerating Circular Product Design at Scale.) - publishing soon!

Love your work!